No Imprisonment of Workers, No Borders!

The basis of any real unity comes from an agreement on certain key ideas. This statement does not grant authority to any party over any other party. We are mutually accountable to each other to uphold these points in order to remain active participants in this united front.

How to join the United Front for Peace in Prisons?

[This statement was drafted by members of the Maoist Internationalist Ministry of Prisons, United Struggle from Within, the East Coast Consolidated Crip Organization, and the Black Order Revolutionary Organization, with input and review from other organizations and individuals working on peace and unity in U.$. prisons. If your organization wishes to join the United Front, you may submit your own statement of unity/support to Under Lock & Key.]

If the last 40 years have proven anything to us, it is that Amerika wants us at war with each other and locked in their prisons. The idea that banging is what we’re just born into, as if we have no power over our own lives, is no longer acceptable if we want to survive. For the next generation to repeat what we have been through would be genocidal. We embrace internationalism because we recognize that most of the people in the world face potentially genocidal conditions under imperialism and that there is strength in numbers. This is a call for peace, unity and understanding amongst the many prison organizations currently in opposition to each other and individual non-gang affiliated comrades alike to take on an approach that utilizes the strength of our numbers in revolutionary struggle.

We have awareness that there’s nothing cool about the hardships we as gang members and petty criminals put ourselves, our families, our communities and each other through. If we have to struggle and if we have to sacrifice then it’s more logical that we put our strength and resources collectively against one target - the oppressor.

Too many of us are already in jail. To engage in reckless behavior that could get us locked up or locked down only helps Amerika control us. Tupac Shakur, who also helped draft a code of principles to unite lumpen organizations, referred to the Thug Life stage of his life and his music as the “high school” phase for ghetto youth. By the time he was locked in prison he was growing and expanding beyond Thug Life, while recognizing it would always be a part of him. He referred to this as his “college” phase, saying that some people never get out of high school. Our comrades often draw parallels between the intellectual growth of college students and prisoners. But prison should not be where certain groups of people must go to learn and grow.

A parallel example is found in the ideology of the Almighty Latin King Queen Nation, which describes its followers passing from the Primitive Stage to the Conservative (or Mummy) Stage to the New King Stage. The Primitive Stage is usually characterized by gang-banging and reckless behavior. The Conservative Stage steps away from previous recklessness, distancing oneself from the whole organization. “The New King recognizes that the time for revolution is at hand… A revolution that will bring freedom to the enslaved, to all Third World People… The New King is the end product of complete awareness, perceiving three hundred and sixty degrees of enlightenment. He strives for world unity. For him, there are no horizons between races, sexes and senseless labels. For him, everything has meaning, human life is placed above materialistic values. He throws himself completely into the battlefield, ready to sacrifice his life for the ones he loves, for the sake of humanization.” (Kingism: Three Stages from The King Manifesto)

Despite our different paths of evolution over the years, all of our organizations share a common history that arose from the need to defend oneself and one’s community in a society that has always kept us as outsiders. It is sad that we must find ourselves in the most horrid of oppressive situations (i.e. control units or death row) before our organizations can begin working together in our common interests. The purpose of this united front is to incorporate that commonality as part of our continued growth. Unity evolves from the inside out. Once we’ve begun to grow as individuals, our first task is to build unity within our group around the principles of the united front.

As we work to build unity with others, we must remember that rumors are tactics of pigs and snitches. Too many people have a habit of talking shit and creating disunity, as if it’s a game. Comrades should know when to speak, where to speak, what to speak, to whom to speak, how to speak and when to keep absolutely silent.

There have been a number of attempts to unite various sets and cliques under one banner for a positive cause. But when such efforts are led by the criminally-minded these causes are only served superficially and the organizations continue to work in the interests of the greed and power of the few.

In the United $tates we are surrounded by wealth and excess, which breeds a sick love for their system of exploitation. Yet success for much of the oppressed nations is still handed out like winning lotto tickets, whether as a boss on the street or a ball player or other entertainer. And therein, we become oppressors of our own community, nation and the rest of the world. Meanwhile, our oppressed peoples as a whole are not allowed to determine their own destinies as nations.

The easier way out of the ghetto is to become overt oppressors by joining the white man’s army. The imperialist wars of aggression are wars against the oppressed nations of the world. We are killed and injured in these wars to help kill and control the oppressed people the world over. To join the military of the oppressor (United $tates) is to betray and sell out our collective peoples.

We fully recognize that whether we are conscious of it or not, we are already “united” – in our suffering and our daily repression. We face the same common enemy. We are trapped in the same oppressive conditions. We wear the same prison clothes, we go to the same hellhole box (isolation), we get brutalized by the same racist pigs. We are one people, no matter your hood, set or nationality. We know “we need unity” – but unity of a different type from the unity we have at present. We want to move from a unity in oppression to unity in serving the people and striving toward national independence.

We cannot wish peace into reality when conditions do not allow for it. When people’s needs aren’t met, there can be no peace. Despite its vast wealth, the system of imperialism chooses profit over meeting humyn needs for the world’s majority. Even here in the richest country in the world there are groups that suffer from the drive for profit. We must build independent institutions to combat the problems plaguing the oppressed populations. This is our unity in action.

We acknowledge that the greater the unity politically and ideologically, the greater our movement becomes in combating national oppression, class oppression, racism and gender oppression. Those who recognize this reality have come together to sign these principles for a united front to demonstrate our agreement on these issues. We are the voiceless and we have a right and a duty to be heard.

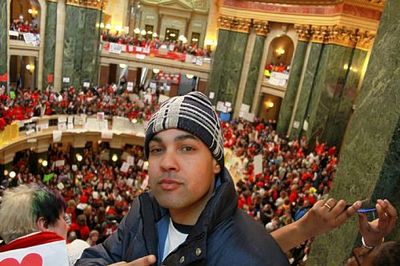

Jasiri X is a hip hop artist from Pittsburgh who raps the news over some dope beats produced by The Grand Architect Paradise Gray of X Clan. The two release these tracks as videos on youtube.com in a series titled “This Week with Jasiri X.” Jasiri X is popular in activist circles, frequently performing and speaking at benefits and rallies. We’ve been bobbing our heads to his tracks since the release of OG3 - Oscar Grant Tribute in January 2009, but in light of his most recent release, American Workers vs. Multi-Billionaires, we decided to take a closer look.

OG3 tells the story of the murder of Oscar Grant and the rebellions following his murder, from the points of view of Oscar Grant and the protesters. Although the facts aren’t 100% correct in OG3, it is a good example of the many tracks Jasiri X has released about police brutality and aggression against Black people in Amerika. A track titled Free the Jena 6 was one of the first that got peoples’ attention, and he continues to shout out victims of police execution and violence by name.

When working on an international piece, Jasiri X correctly draws connections between police brutality here and imperial aggression against Third World peoples around the world. He recently released a track about the uprisings in Egypt with M-1 of Dead Prez, titled We All Shall Be Free!

Despite his revolutionary lean, Jasiri X still holds on to his Amerikanism on several issues, which comes up big time in American Workers vs. Multi-Billionaires. The video for this song was shot inside the capitol building in Madison, Wisconsin, against a backdrop of labor aristocrats raising a stink to keep their “fair share” of the imperialist pie. The title implies that a line is being drawn between Amerikan “workers” and the capitalist multi-billionaires with this union busting legislation. However, as outlined in several articles and books(1) Amerikan “workers” are actually fundamentally allied with the imperialist, capitalist class on an international level. It is only because of the pillage of resources and lives in the Third World that the government employees in Wisconsin even have health care in the first place. Defending this “right” to health care is essentially the same thing as supporting Amerikan wars, which Jasiri X says he is against. History has shown that the multi-billionaires won’t give up theirs without a fight.

“When did the American worker become the enemy?

Why is wanting a living wage such a penalty?”

- Jasiri X from “American Workers vs. Multi-Billionaires”

The Amerikan “worker,” or labor aristocrat, is the enemy of the majority of the world’s people because their lives are subsidized by the economic exploitation of the Third World. Third World peoples’ sweat, blood, and lives are wasted to pay for the Amerikan “worker’s” pensions and health care. This is because most of the “work” that Amerikans do does not generate value; we have a service-based economy. The only reason our society has such a disproportionately high “living wage” (as if those who make less die) is because we are comfortable swinging our weight around in imperialist wars of aggression to extract wealth from the Third World. Jasiri X seems to be opposed to this extraction of wealth, but does not make the connection that Amerikan “workers” are directly benefiting from it, and not just the multi-billionaires.

Jasiri X seems to adhere to an anti-racist model of social change. Besides being supported by an incorrect analysis of history, it also has him defending Obama as a Black man, rather than attacking him as the chosen leader of the largest and most aggressive imperialist country in the world. Jasiri X correctly pins Obama as an ally of the Amerikan people; their key to a comfortable lifestyle and fat retirement plan. But as an ally of the oppressed, Jasiri X should accept that Obama, and the labor aristocracy, are enemies of the majority of the world’s people, and leave patriotism behind. Agitating for the betterment of people in Haiti, Palestine, Egypt, Iraq, etc. as Jasiri X does through some of his raps, while at the same time defending Obama and the Amerikan “worker,” is a recipe for stagnation. If we want to end oppression the world over, we need to have a clear idea of who are our friends and who are our enemies.

[Leaders] realize that the success of the struggle presupposes clear objectives, a definite methodology and above all the need for the mass of the people to realize that their unorganized efforts can only be a temporary dynamic. You can hold out for three days – maybe even for three months – on the strength of the admixture of sheer resentment contained in the mass of the people; but you won’t win a national war, you’ll never overthrow the terrible enemy machine, and you won’t change human beings if you forget to raise the standard of consciousness of the rank-and-file. Neither stubborn courage nor fine slogans are enough. - Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, p. 136, chap. 2, paragraph 57.

Starting in Tunisia on December 17, and spreading across the region in January and February, the people of north Africa and the Middle East are taking to the streets to fight brutal dictatorships in their respective countries. Taken by surprise by the force and longevity of these protest movements, the various imperialist-backed regimes are working hard to come up with changes that will pacify the people without fundamentally changing the system. These just struggles of the people are primarily targeting the figureheads in government, but the real problem lies in the system itself and at this stage we are only seeing some shuffling of the leadership.

Protests are sweeping across the region as the people are emboldened and inspired by the actions and results of those in neighboring countries, even moving further south into other parts of Africa. As this article is being written, there are reports of people’s uprisings in Bahrain, Libya, Iran, Yemen, Iraq, Kuwait, Algeria, Djibouti, Syria, Morocco and Jordan. In other parts of Africa, less visible in the media, popular revolts are also happening in Sudan, Gabon and Ethiopia.(1) Protesters are facing violent repression by the governments in most of these countries.

The response in the United $tates has been strong condemnation of Mubarak and other leaders targeted by protests (among those paying attention). Arabs may falsely look to Amerikans as friends in their current struggles. But where was this Amerikan “support” for the last thirty years as their country bank-rolled Mubarak with billions of dollars? In reality, their reaction is a sick reminder of what went down in Iraq. The same seething opposition to Mubarak was aimed at Saddam Hussein, resulting in the deaths of millions of Iraqis and the destruction of one of the most developed Arab countries. Iraq is just one example to demonstrate how Amerikan racism quickly lends itself to popular support for militarism, the savior of post-WWII U.$. global dominance.

There are many differences between these mostly Arabic-speaking countries, but the one common enemy of the people there is the enemy of the people throughout the world: imperialism. Capitalism is a system that is defined by the ownership of the means of production (factories, farms, etc.) by the wealthy few who we call the bourgeoisie, and who exploit the majority of the people (the workers, also called the proletariat) to generate profit for the owners. Imperialism is the global stage of capitalism where the territories of the world have been divided up and exploited for profit. Under imperialism, the economy in each country no longer operates independently, and what happens in one country has repercussions around the world. Because of this global interdependence, events in the Middle East and north Africa are very significant to the Amerikan and European capitalists, and are related to events in the global economy.

The question of real change hinges on whether the exploited countries that are now mobilizing stay within the U.$.-dominated economic structure, or whether they look to each other and turn their back on the exploiter nations. While militarily and politically controlled by the United $tates, their economic relationship to imperialism is dominated by the European Union who was responsible for 50% of trade for countries in the southern Mediterranean region in 1998. A mere 3% of their trade was with each other that year.(2) In 2009, these percentages had not changed, despite the lofty promises of the Euro-Mediterranean Free Trade Area to develop trade between Arab countries.(3) Tunisia, where the first spark was lit, had 78% of its exports and 72% of its imports with the European Union. Compare these numbers to the ASEAN and MERCOSUR regional trade groups, also made up of predominately Third World countries, which had about 25% of their trade internally.(4)

The problem with Europe dominating trade in the region is based in the theories of “unequal exchange” that lead trade between imperialist and exploited countries to be inherently exploitative. Part of this is because the north African countries mostly produce agricultural goods and textiles, which they trade for manufactured goods from Europe. The former are more susceptible to manipulations in commodities markets that, of course, are controlled by the imperialist finance capitalists. The latter are priced high enough to pay European wages, resulting in a transfer of surplus value from the north African nations to the European workers.

In order to develop industries for the European market, these countries have been forced to accept Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) from the various world banking systems (World Bank, International Monetary Fund). This has further tied the governments to imperialist interests over the years, as SAPs have many strings attached. The loans themselves, which are larger in this region than for the average Third World country (5), serve to transfer vast amounts of wealth from the debtor nations to the lender nations in the form of interest payments.

Countries in the Middle East and north Africa generally have greater relative wealth compared with Third World countries in the rest of Africa, Asia and Latin America. As a result the people in these countries enjoy higher levels of education, better health and fewer people living in poverty.(see World Bank, World Health Organization and CIA statistics) General trends since WWII are a growing middle class with an emigrant population that expanded and benefited from European reconstruction up to the 1980s. Since then immigration restrictions have increased in the European countries, particularly connected to “security” concerns after 9/11. The north African countries relate to the European Union similar to how Mexico does to the United $tates, but Mexico remains more economically independent by comparison. These uprisings are certainly connected to the growing population and the shrinking job market with slower migration to the EU.

Locally, there are economic differences within the region that are important as well. Other than the stick of oppressive regimes, some governments in the region have been able to use their oil revenues as a carrot to slow proletarian unity. Even so, extreme international debt, increasing unemployment with decreasing migration opportunities and the overall levels of poverty indicate that these countries are part of the global proletariat.

The recent economic crisis demonstrates the tenuous hold the governments of the Middle East and north African countries had on their people. Because imperialism is a global system with money, raw material and consumer goods produced and exchanged on a global market, economic crises happen on a global scale. The economic crisis of the past few years has affected the economy of this region with rising cost of living and increased unemployment rates. In particular food prices have reached unprecedented highs in the past few months.(6) One might think this would help the large agricultural sectors in these countries. However, food prices affect the Third World disproportionately because of the portion of their income spent on food and the form their food is consumed in. On top of this, all of these countries have come to import much of their cereal staples as their economies have been structured to produce for European consumption.

Reliable economic statistics are difficult to find for this region. Estimates of unemployment in any country can range from under 10% up to 40% and even higher, and there is similar variability in estimates of the portion of the population living below the poverty level. But all agree that both unemployment and poverty have been on the rise in the past two years. We suspect this trend dates back further with the decrease in migration opportunities mentioned above.

In Egypt about two-thirds of the population is under age 30 and more than 85% of these youth are unemployed. About 40% of Egypt’s population lives on less than $2 a day.(7)

The middle class in these countries, who enjoy some economic advantages, are sliding further into poverty. This group is particularly large in Tunisia and Egypt compared to many other countries in the region.(8) In Egypt the middle class increased from 10% to 30% of the population in the second half of the 20th century, with half of those people being “upper” middle class.(9) This class has been closely linked to the rise of NGOs encouraged by the European-led Euro-Mediterranean Free Trade Area. They know that it is possible for them to have a better standard of living and enjoy more political freedom without a complete overthrow of the capitalist system. And so we saw many of the leaders and participants in the recent protests demand better conditions for themselves, but generally leave out the demands of the proletariat.

In fact, some middle class leaders, like Wael Ghonim (an Egyptian Google employee who was a vocal leader in the fight against Mubarak), are calling for striking workers to go back to work now that Mubarak has stepped down, effectively opposing the demands and struggles of the Egyptian proletariat. Without the leadership of the proletariat, who have never had significant benefits from imperialism, these protests end up representing middle class demands to shuffle the capitalist deck and put another imperialist-lackey government in place. The result might be a slight improvement in middle class conditions but the proletariat ends up right back where they started.

In Tunisia and Egypt, where the uprisings started, the leadership and many of the activists were from the educated middle class youth.(10) In Tunisia people were inspired to act after the suicide of Mohammed Bouazizi, an impoverished young vegetable street seller supporting an extended family of eight. He set himself on fire in a public place on December 17 after the police confiscated his produce because he would not pay a bribe. Like many youth in Tunisia, Bouazizi was unable to find a job after school. He completed the equivalent of Amerikan high school, but there are many Tunisian youth who graduate from college and are still unable to find work.

The relative calm in the heavy oil producing region that includes Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman and Qatar underscores the key role of economics and class in these events. These countries enjoy a much higher economic level than the rest of the region, as a direct result of the consumerist First World’s dependence on their natural resources. Only Libya joins these countries in having a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita above $5000, while all others in the region are below that level.(11) That’s compared to a GNI in the U.$ of $46,730.(12)

One economic factor that has not made the news much and which does not seem to be a focus of the protesters so far, is the importing of foreign labor to do the worst jobs in the wealthy oil-producing countries. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (consisting of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE, Bahrain, Kuwait and the Sultanate of Oman) there are an estimated 10 million foreign workers and 3 million of their family members living in these countries.(13) This was used as a carrot to the proletariat who were losing opportunities to work in the European Union. Egypt in particular encouraged this emigration of workers.

To belittle the just struggles of people around the world, typical imperialist media is referring to the recent uprisings as “unrest,” as if the people just need to be calmed down to bring things back to normal. On the other side, many protesters and their supporters are calling these movements revolutions. For communists, the label “revolution” is used to describe movements fighting for fundamental change in the economic structure. In the world today, that means fighting to overthrow imperialism and for the establishment of socialism so that we can implement a system where the people control the means of production, taking that power and wealth out of the hands of just a few people.

The global system of imperialism puts the nations of the Middle East and north Africa on the side of the oppressed. These nations have comprador leaders running their governments, who get rich by working for imperialist masters. Yet these struggles are very focused on the governments in power in each country without making these broader connections. Until the people make a break with imperialist control, changes in local governments won’t lead to liberation of the people.

Further, we have heard much from both organizers and the press about social media (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) as a tool of the revolution. These tools are celebrated as a replacement for leadership. It is true that the internet is a useful tool for sharing information and organizing, and decentralization makes it harder to repress a movement. But the lack of ideological unity leads to the lowest common denominator, and very few real demands from the people. No doubt “Mubarak out” is not all the Egyptian people can rally around, but without centralized leadership it is hard for the people to come together to generate other demands.

Related to the use of social media, it is worth underscoring the value of information that came from Wikileaks to help galvanize the people to action in these countries; the corruption and opulence of the leaders described in cables leaked at the end of 2010 no doubt helped inspire the struggles.(14)

Egypt provides a good example of why we would not call these protest movements “revolutions.” The Egyptian people forced President Mubarak out of the country, but accepted his replacement with the Supreme Council of the Military - essentially one military dictatorship was replaced by another. One of the key members of this Council is Sueliman, the CIA point man in the country and head of the Egyptian general intelligence service. He ran secret prisons for the United $tates and persynally participated in the torturing of those prisoners.

Tunisia is also a good example of the lack of fundamental revolutionary change. Tunisia’s president of 23 years, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, stepped down on January 14 and fled to Saudi Arabia. But members of Ben Ali’s corrupt party remained in positions of power throughout the government and protests continue.

In State and Revolution Lenin wrote that the revolution must set a goal “not of improving the state machine, but of smashing and destroying it.” The protests and peoples’ struggles in the Middle East and Africa reinforce the importance of this message as we see the sacrifice of life in so many countries resulting in only cosmetic changes in governments.

The United $tates is the biggest imperialist power in the world today; it controls the largest number and most wealth-producing territories in the world. Just as the economic crises of imperialism affect the rest of the world, political uprisings around the world affect the United $tates. The capitalist corporations who have factories and investments in this region have a strong financial interest in stability and a government that will allow them to continue to exploit the resources and labor. And with capitalism’s constant need to expand, any shrinking of the imperialist sphere of influence will help trigger future crises faster.

The Amerikan military interest in this region relies on having some strong puppet governments as allies to defend the interests of Amerikan imperialism and hold off the independent aspirations of the regional capitalists. This includes managing the planet’s largest oil reserves, which is important for U.$. control of the European Union, and defending their #1 lackey - Israel.

Tunisia is a long-standing ally of the United $tates, cooperating with Amerikan “anti-terrorism” to maintain Amerikan imperialist power in the region. Other imperialist powers also have a strong interest in the dictatorships in Tunisia including France whose government shipped tear gas grenades to Tunis on January 12 to help Ben Ali fight the protesters.(15)

Bahrain is a close U.$. ally, home to the U.$. Navy’s Fifth Fleet.(16)

Egypt has been second only to Israel in the amount of U.$. aid it gets since 1979, at about $2 billion a year. The majority of this money, about $1.3 billion a year, goes to the Egyptian military.(17) Further, the United $tates trains the Egyptian military each year in combined military exercises and deployments of U.$. troops to Egypt.(18) So for Amerika, the Supreme Council of the Military taking power in Egypt is a perfectly acceptable “change.” To shore up the new regime and its relationship with the United $tates, Secretary of State Clinton announced on February 18 that the United $tates would give $150 million in aid to Egypt to help with economic problems and “ensure an orderly, democratic transition.” In exchange, the Council has already pledged to uphold the 1979 peace accords with Israel. Prior to 1979, much of the Arab world was engaged in long periods of wars with the settler state.

United $tates aid to countries in this region is centered around Israel. The countries closest geographically to Israel are the biggest recipients of Amerikan money, a good way to keep control of the area surrounding the biggest Amerikan ally. In addition to Egypt and Israel, Jordan ($843 million) and Lebanon ($238 million) received sizable economic and military aid packages in 2010.(19) Compared to these numbers, “aid” to the rest of the region is significantly smaller with notable recipients including Yemen ($67M), Morocco ($35M), Bahrain ($21M) and Tunisia ($19M). The United $tates gives “aid” in exchange for economic, military and political influence.

The global economic crisis clearly affects imperialist countries like the United $tates just like it does other countries of the world, but we don’t see the people in this country rising up to take over Washington, DC and demanding a change in government. Like the Middle East, the youth of Amerika are having a harder time finding jobs after graduation from college. But unlike their counterparts in the Middle East, Amerikan youth and their families do not face starvation when this happens.

Some people are drawing comparisons between the widespread protests by labor unions in Wisconsin and the events in Tunisia and Egypt. These events do give us a good basis for comparison to underscore the differences between imperialist countries and the Third World. Amerikan wealth is so much greater than the rest of the world (U.$. GDP per capita = $46,436); even compared to oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia (GDP = $24,200). GDP does not account for the distribution of wealth, but in the United $tates the median household income in 2008 was $52,029. This number is not inflated by the extreme wealth of a few individuals, it represents the middle point in income for households in this country.

On the surface, unemployment statistics for the United $tates appear similar to some numbers for countries in the Middle East and north Africa. In 2008, 13.2% of the population was unemployed in the United $tates based on the latest census data.(20) However, with income levels so much higher in Amerika, unemployment doesn’t mean an immediate plunge into poverty and starvation. For youth in this country, there is the safety net of moving back in with parents if there is no immediate post-college job.

Similarly, U.$. poverty statistics appear quite high, comparable to rates in the Middle East and north Africa, at 14.3% in 2009. But this poverty rate uses chauvinistic standards of poverty for Amerikans. The U.$. census bureau puts the poverty level of a single individual with no dependents at $11,161.(21) Much higher than the statistics that look at the portion of the population living at $2 or $1.25 per day (adjusted for differences in purchasing power). Wisconsin public teachers average salaries of about $48k per year.

The Leading Light Communist Organization produced some clear economic comparisons between Egypt and the U.$.: “The bottom 90% of income earners in Egypt make only half as much (roughly $5,000 USD annually) as the bottom 10% of income earners in the U.$. (roughly [$]10,000), per capita distribution. Depending on the figures used, an egalitarian distribution of the global social product is anywhere between $6,000 and $11,000 per capita annually. This does not even account for other inequalities between an exploiter country and an exploited country, such as infrastructure, housing, productive forces, quality and diversity of consumer goods, etc.”(22)

In the United $tates it is possible for the elite to enjoy their millionaire lifestyles while the majority of the workers are kept in relative luxury with salaries that exceed the value of their labor. This is possible because other countries, like those in the Middle East and Africa, are supplying the exploited workforce that generates profits to be brought home and shared with Amerikan workers. Even Amerikan workers who are unemployed and struggling to pay bills are not rallying for an end to the economic system of capitalism. They are just demanding more corporate taxes and less CEO bonuses. In other words they want a bigger piece of the imperialist pie: money that comes at the expense of the Third World workers. These same Amerikan workers rally behind their government in wars of aggression around the world, overwhelmingly supporting the fight against the Al-Qaeda boogeyman in Arab clothing.

Whether in Madison or Cairo, signs implying that Wisconsin is the Tunisia of north Amerika are examples of what we call “false internationalism” on both sides of the divide between rich and poor nations. Combating false internationalism, which is inherent in any pro-Amerikanism in the Third World, is part of the fight against revisionism in general.

What no one can deny is the connection between the mass mobilizations across the Arab world. That this represents a reawakening of pan-Arabism is both clear and promising for the anti-imperialist struggle. Even non-Arab groups in north Africa that have felt marginalized will benefit from the greater internationalist consciousness and inherent anti-imperialism with an Arabic-speaking world united against First World exploitation and interference.

Of course, Palestine also stands to benefit from these movements. The colonial dominance of Palestine has long been a lightning rod issue for the Arab world, that only the U.$. puppet regimes (particularly in Egypt) have been able to repress.

Everyone wants to know what’s next. While the media can create hype about the “successful revolutions” in Tunisia and Egypt, this is just the beginning if there is to be any real change. Regional unity needs to lead to more economic cooperation and self-sufficiency and to unlink the economies of the Arab countries from U.$. and European imperialism. Without that, the wealth continues to flow out of the region to the First World.

As Frantz Fanon discussed extensively in writing about colonial Algeria, the spontaneous violence of the masses must be transformed into an organized, conscious, national violence to rid the colony of the colonizer. Unfortunately, his vision was not realized in the revolutionary upsurge that he lived through in north Africa and neo-colonialism became the rule across the continent. Today, the masses know that imperialism in Brown/Black face is no better. As fast as the protests spread, they must continue to spread to the masses of the Arab world before we will see an independent and self-determined people.

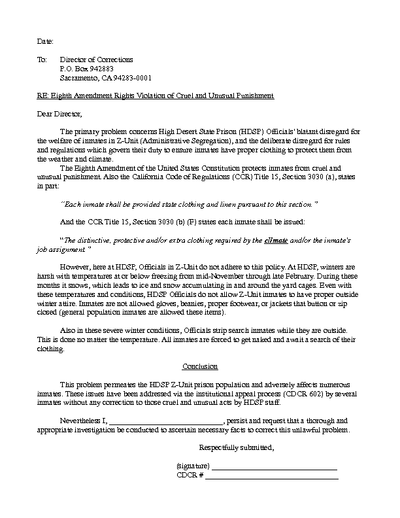

Mail the petition to your loved ones and comrades in High Desert State Prison’s Z-Unit (administrative segregation) who are experiencing brutality and cruel living conditions. Send them extra copies to share! For more information on this campaign, click here.

Prisoners should send a copy of the signed petition to each of the addresses below. Supporters should send letters on behalf of prisoners.

Prison Law Office

General Delivery

San Quentin, CA 94964Internal Affairs CDCR

10111 Old Placerville Rd, Ste 200

Sacramento, CA 95872CDCR Office of Ombudsman

1515 S Street, Room 540 N

Sacramento, CA 95811U.S. Department of Justice - Civil Rights Division

Special Litigation Section

950 Pennsylvania Ave, NW, PHB

Washington DC 20530Office of Inspector General

HOTLINE

PO Box 9778

Arlington, VA 22219

And send MIM(Prisons) copies of any responses you receive!

MIM(Prisons), USW

PO Box 40799

San Francisco, CA 94140

Mail the petition to your loved ones inside who are experiencing issues with the grievance procedure. Send them extra copies to share! For more info on this campaign, click here.

Prisoners should send a copy of the signed petition to each of the addresses below. Supporters should send letters on behalf of prisoners.

Warden

(specific to your facility)Oklahoma State Jail Inspector, Don Garrison

1000 N.E. 10th St.,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73117-1299ODOC Office of Internal Affairs

Oklahoma City Office

3400 Martin Luther King Avenue

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73111-4298Office of Inspector General

HOTLINE

P.O. Box 9778

Arlington, Virginia 22219United States Department of Justice - Civil Rights Division

Special Litigation Section

950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, PHB

Washington, D.C. 20530Oklahoma Citizens United for Rehabilitation of Errants

(OK-CURE)

P.O. Box 9741

Tulsa, OK 74157-0741

And send MIM(Prisons) copies of any responses you receive!

MIM(Prisons), USW

PO Box 40799

San Francisco, CA 94140

Petition updated July 2012, October 2017

Mail the petition to your loved ones and comrades inside who are experiencing issues with the grievance procedure or censorship of music and literature. Send them extra copies to share! For more info on this campaign, click here.

Prisoners should send a copy of the signed petition to each of the addresses below. Supporters should send letters on behalf of prisoners.

Tom Clements, Director of Adult Institutions

P.O. Box 236

Jefferson City, MO 65101Chris Pickering, Inspector General (MO DOC)

P.O. Box 236

Jefferson City, MO 65101U.S. Department of Justice

PhB 950 Pennsylvania Ave, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20530Marianne Atwell, Director of Offender Rehabilitative Services (Missouri)

P.O. Box 236

Jerrerson City, MO 65101

And send MIM(Prisons) copies of any responses you receive!

MIM(Prisons), USW

PO Box 40799

San Francisco, CA 94140

The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta

Mario Vargas Llosa

Aventura press, 1986

Peruvian author Mario Vargas Llosa won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2010. Widely known as an author who writes about political events in Peru, and takes a vocal position on politics throughout Latin America, this review only addresses one of the many books he has written. But it is a good example of the political views of Vargas Llosa whose politics have made him an enemy of the people for many years. Vargas Llosa claims that he supported revolutionary politics earlier in his life, but if true, he firmly and thoroughly changed that and works hard as a critic of people’s movements and a supporter of imperialist so-called democracy. He has written many works of both fiction and non-fiction, and lost a bid for president of Peru in 1990, during the height of the Peruvian Communist Party’s fight for liberation of the Peruvian people, to Alberto Fujimori.

After being named the Nobel winner, Vargas Llosa said, “It’s very difficult for a Latin American writer to avoid politics. Literature is an expression of life, and you cannot eradicate politics from life.”(1) We would agree with that statement, and as we demonstrate in this review, The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta is a good demonstration of Vargas Llosa’s reactionary politics.

In his acceptance speech for the Nobel prize, Vargas Llosa commented

extensively on the “terrorists” in the world today who are the enemy of

what he calls “liberal democracy” (capitalism). Spouting the best

pro-imperialist rhetoric, Vargas Llosa makes the case for imperialist

militarism with lies about the freedom and beauty of capitalist

so-called democracy:

“Since every period has its horrors, ours is the age of fanatics, of suicide terrorists, an ancient species convinced that by killing they earn heaven, that the blood of innocents washes away collective affronts, corrects injustices, and imposes truth on false beliefs. Every day, all over the world, countless victims are sacrificed by those who feel they possess absolute truths. With the collapse of totalitarian empires, we believed that living together, peace, pluralism, and human rights would gain the ascendancy and the world would leave behind holocausts, genocides, invasions, and wars of extermination. None of that has occurred. New forms of barbarism flourish, incited by fanaticism, and with the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, we cannot overlook the fact that any small faction of crazed redeemers may one day provoke a nuclear cataclysm. We have to thwart them, confront them, and defeat them. There aren’t many, although the tumult of their crimes resounds all over the planet and the nightmares they provoke overwhelm us with dread. We should not allow ourselves to be intimidated by those who want to snatch away the freedom we have been acquiring over the long course of civilization. Let us defend the liberal democracy that, with all its limitations, continues to signify political pluralism, coexistence, tolerance, human rights, respect for criticism, legality, free elections, alternation in power, everything that has been taking us out of a savage life and bringing us closer – though we will never attain it – to the beautiful, perfect life literature devises, the one we can deserve only by inventing, writing, and reading it. By confronting homicidal fanatics we defend our right to dream and to make our dreams reality.”

Vargas Llosa went on to talk about his political views:

“In my youth, like many writers of my generation, I was a Marxist and believed socialism would be the remedy for the exploitation and social injustices that were becoming more severe in my country, in Latin America, and in the rest of the Third World. My disillusion with statism and collectivism and my transition to the democrat and liberal that I am – that I try to be – was long and difficult and carried out slowly as a consequence of episodes like the conversion of the Cuban Revolution, about which I initially had been enthusiastic, to the authoritarian, vertical model of the Soviet Union; the testimony of dissidents who managed to slip past the barbed wire fences of the Gulag; the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the nations of the Warsaw Pact; and because of thinkers like Raymond Aron, Jean Francois Rével, Isaiah Berlin, and Karl Popper, to whom I owe my reevaluation of democratic culture and open societies. Those masters were an example of lucidity and gallant courage when the intelligentsia of the West, as a result of frivolity or opportunism, appeared to have succumbed to the spell of Soviet socialism or, even worse, to the bloody witches’ Sabbath of the Chinese Cultural Revolution.”

Finally, Vargas Llosa made clear his support for the neocolonial governments in Latin America, pretending that they represent “functioning” democracy in the interests of the people and “supported by a broad popular consensus.”:

“We are afflicted with fewer dictatorships than before, only Cuba and her named successor, Venezuela, and some pseudo populist, clownish democracies like those in Bolivia and Nicaragua. But in the rest of the continent democracy is functioning, supported by a broad popular consensus, and for the first time in our history, as in Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and almost all of Central America, we have a left and a right that respect legality, the freedom to criticize, elections, and succession in power. That is the right road, and if it stays on it, combats insidious corruption, and continues to integrate with the world, Latin America will finally stop being the continent of the future and become the continent of the present.”

This book is indicative of Vargas Llosa’s work which does greater disservice to the revolutionary movement in Peru than those who write bourgeois fiction without pretending to have historical context or political purpose. The novel reviews the life of a fictional revolutionary activist in Peru in the 1950s who participated in a small focoist uprising before ending up in prison. The book describes revolutionary parties as all small marginalized groups wasting their time studying dead guys and debating theory. And it leaves the reader questioning the commitment of all who participate in revolutionary politics, assuming that everyone sells out somehow to pursue their own interests in the end. The peasants and workers are virtually ignored in the book, portrayed only as pawns in the work done by activists.

This novel focuses on a small Trotskyist party, the product of several splits in previous Trotskyist groups, and specifically on one of the party members, Alejandro Mayta. Interestingly, in a brief description of how Mayta ended up in this party, Vargas Llosa describes his movement from group to group, each time rejecting the previous one as not correct enough politically, until he ended up with the Trotskyists as the most pure political line he could find. MIM(Prisons) has some agreement with this description in that Trotskyism is pure idealism and it appeals to those who don’t like to get their hands dirty with the realities of revolutionary politics.

Eventually Mayta deserts the Trotskyists to join up with a focoist movement in the mountains that is going to take armed action. He is galvanized by the idea of real action rather than the talk that his Trotskyist group has been engaging in for years. He is kicked out of his party, who consider the action premature, and also because Mayta has approached the Stalinists to participate in and support the focoist action.

Focoists believe that the armed actions of a small group of people will spark the masses to join the revolution. This is an incorrect view of revolutionary strategy. History has demonstrated that small groups of insurgents are not sufficient to bring about revolution; successful revolutions have come through the hard work of organizing the masses. As inspiration, many focoists look to the Cuban revolution, and Castro is mentioned repeatedly in the book. But the Cuban revolution is the only example focoists have of anything resembling success, and while that revolution did deliver a blow to U.$. imperialism, it created a state-capitalist country dependent on the Soviet Union.(2) Like other focoist actions, Mayta’s small group is captured during their armed insurrection. And there is much debate about whether desertion, betrayal, or just poor planning led to their failure.

A recurring theme in this book is the claim by the narrator that the truth of history is impossible to determine. In interviewing people about the life of Mayta the narrator gets conflicting stories from everyone he talks to, and is unable to figure out exactly what happened. This nihilist position encourages people to just give up rather than seeking to understand and interpret history to help forward progress in the future. Ironically Vargas Llosa thinks he knows the definitive truth about the history of politics in many countries as he interprets history through the lens of the imperialists.

Through this fictional novel, Vargas Llosa manages to attack a vast range of revolutionary theories and practices, and leave the reader disillusioned and without hope for a better future for the people of Peru. He does not try to hide the poverty and despair that is the everyday reality of life for the Peruvian people, but condemns revolutionaries, politicians, and everyone else to failure in a maze of corruption, collaboration and irrelevant theories. There is no redeeming political value to this book which could depress even the most militant of activists.

One of the important tasks of intelligence is to develop a map of the networks of those being surveilled. This simple fact is too often ignored in our culture today, where technology has electronically and permanently connected us. What used to at least require a warrant sent to your phone company is now public information for most people in the United $tates today who regularly use social networking through the internet and their cell phones.

To an extent, the omnipresence of these technologies in Amerikan lives have made people more conscious of this vulnerability. Yet, very few involved in voicing opinions in favor of a world without oppression actually incorporate this knowledge into their practice. Largely this is a class issue where the petty bourgeoisie feels safe living in a bourgeois democracy. In much more remote parts of the world, there is a greater understanding of the need for encryption and shielding one’s identity because the consequences are life and death.

MIM(Prisons) doesn’t engage in baseless alarmism to mobilize people, but this is a case where you should be considering worst case scenarios, like how a fascist government might carry out a witch-hunt for “communists” and “terrorists” using public information on the internet.

When struggling with allies about security, we regularly get the response, “I’m already on all their lists.” It’s often a point of pride to say this. But the oppressed know that getting on a list has real consequences. In addition, anyone who has studied COINTELPRO knows that the government is interested in more than just your name, but our sense of comfort here in the belly of the beast leads to lazy practices and nihilistic attitudes towards security.

Like we said, this isn’t about persecuting people for thought crimes,

though that has happened countless times to U.$. citizens as a result of

information posted on the internet. COINTELPRO was about disrupting

movements. It is far too easy for a fat pig sitting at his desk to know

who young activists are in touch with, and what they are doing when and

where. Using this information the imperialist state can be very

strategic in how it uses its various tools of repression. With the

current state of security culture, technology has given the oppressor

the advantage, but this does not have to be the case.

As we work on finishing the first draft of this article, the U.$. media is talking about popular demonstrations against governments in Tunisia and Egypt and their use of Twitter and Facebook. Tweeting is a good way to mobilize a flash mob; it is not a good way to build people’s power. It is about as effective as banging a pot in the street. While we don’t mean to dismiss these recent movements in particular, there is plenty of history to show that spontaneous demonstrations do not save lives or improve conditions – capitalism continues on.

We’ve already addressed some of the class issues surrounding the dependence on technology like Twitter elsewhere. Twitter is also an example of corporations defining cultural trends. It almost seems there was a law passed last year that every corporate media entity had to mention Twitter once every 20 minutes on their programming. This free advertising should raise questions around a company that has already openly worked with the U.$. government to overthrow foreign regimes and repress resistance within this country. Despite arrests for such activities, people continue to use Twitter to report from protests in the U.$. without any attempt to cloak the identities of themselves or others involved. Meanwhile, Twitter remains mainly a tool to promote capitalist consumption through advertising.(1)

Speculation aside, it is not the intents of the corporations that we should fear (or rely on); it is the nature of the technology that makes us vulnerable. An independent, nonprofit, open-source social network does not address the main problem here, which is internet-based, public social networking itself.

More recently, the trend is to be able to Tweet, Facebook and Google on your phone. Mobile phones are generally attached to our identity and track your location at all times, while allowing remote monitoring of voice, video (which is generally ubiquitous on phones these days) and of course any worldwide web traffic. While this information would nominally require a warrant, in recent years AT&T has complained that the National Security Agencies requests for these wiretaps have become overly burdensome on the monopolizing telecommunications company, indicating that such wiretapping is far from rare.

Other than building networks, spies like to build profiles of individuals. Today’s mobile phones and computers are walking profiles on many Amerikans. Even if you don’t use a “smart” phone, if you don’t separate your work from your persynal life you are exposing yourself. Every time you do a Google search while logged into Gmail, or access information through Facebook, your activity is connected to your identity. And of course, any internet activity from home is connected to your IP address.

There is a tendency that jumps on every trend, saying “if only we could get an ad that looks like that, if only we could get a Facebook group, if only we could produce hot music” then the masses would listen. A real revolutionary culture needs to be setting the trends and not just copying bourgeois forms and relying on bourgeois institutions. Without independent institutions of the oppressed we have no power over the message we put out and the work that gets done in the name of social progress.

Again, for those who were born into this culture of social networking through the internet, you need to rethink your relationship to the bourgeois institutions that shape your life.

We are not arguing against using the internet or other technology. We are only pushing people to understand the potential and likely consequences before they use it. MIM made great inroads by being a trendsetter in online publishing. Today’s technology makes it easier and safer to use the internet, if you study how to do it correctly.

If you don’t have the patience to learn internet security or don’t believe in it because “Big Brother knows all,” then don’t go online. There should be Maoist work that is not known to the internet. We must combat the thinking that “it can be Googled, therefore it exists.” The internet should be a place to study, to find answers, to debate and to agitate in the realm of ideas. It should not provide a quick and easy snapshot of who we are, what we’re doing, when, where or how many we are.

While cell phone cameras were celebrated in the exposure of the assassination of Oscar Grant by BART police in Oakland, California, they are also helping the police do their job every day. It is hard to go to any sort of political event without being surveilled by dozens of unidentified people. This means that 1) the pigs can sit on their asses looking at Indymedia websites and watching amateur videos on YouTube to see who is frequenting what events, and 2) undercover (or not) pigs can be very open in their efforts to record people at these events.

Closed meetings should not even allow cell phones in the proximity of the meeting. That may be difficult for events open to the public, but people should not be able to come in and record without any accountability. And if you want to record your own events for later use, don’t record people that have not given their permission. People recording the audience should be treated with suspicion and should be stopped.

All of this is connected to who are our friends and who are our enemies. Anti-imperialist comrades should weigh the costs and benefits of doing outreach at events that are swamped with strong Amerikanism. The cell strategy should be studied and applied in a way that one only organizes with those one knows. And one should learn to swim in the sea of people they find themselves amongst. The sea we have to swim in in North America is a sea of white nationalism, so blending in isn’t always appealing, but it is that much more important. Relying on the masses means looking to the world’s majority who have an interest in overthrowing imperialism. Being part of the struggles of the real masses cannot happen through Tweets and Facebook groups. Building a strong movement requires keeping a distance from these institutions of the oppressor and building our own infrastructure.