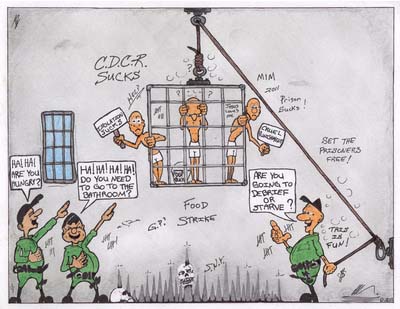

No Real Change, Hunger Strike Continues

On September 26, prisoners in Pelican Bay State Prison will resume their indefinite hunger strike after 2 months of hiatus, during which they negotiated with the state. The strike began on July 1, sweeping across California, and was put on hold by organizers on July 21, after 3 full weeks of fasting. Multiple prisoner negotiators from Pelican Bay have confirmed that Scott Kernan of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) promised the 5 demands would be met, but that they needed 2 to 3 weeks to comply. That window of time has long since passed, and comrades are gearing up for what promises to be a longer stretch with no food.

In a statement from one strike leader announcing the September 26 restart, he stated:

I appreciate the time and love you all have given to us and you can believe that we will not yield until justice is achieved. We went into this trying to save lives, if possible, but we see now that there will have to be casualties on our side and we all know that power concedes to no one without demands.(1)

On August 23, state legislator Tom Ammiano headed a hearing on conditions in California’s SHUs and on the validation process that gets people placed there. It echoed previous hearings that did not stop torture in the SHU. He promised he would push the issue further than it has gone in the past, but like the reforms given by the CDCR, this is too little too late as comrades who have faced decades in these torture cells take this struggle to the next level.

The Truth About the Negotiations

The strike didn’t end over some beanies and calendars. Letters that came from the leaders after the message was sent that the strike ended were very clear that they were only giving the state time to meet their demands before they would restart the food strike. Those in D-Corridor and other SHU prisoners aren’t done yet.

The initial story that came out of limited communications between the inside and outside negotiation teams was that the strike had ended, period, in return for beanies, calendars, proctored exams and a promise to investigate the major complaints of the strikers. The extreme limits put on the outside negotiation team, who were only granted access to the strikers on a couple brief occasions, allowed the state to control how the negotiations were portrayed. As a result, many across the state were let down by the misleading reports that first came out, because the strikers had pledged to strike until all 5 demands were met.

It has since come to light that Scott Kernan circulated a fake version of the five demands,(2) and that prisoners received notices that they had broken the rules by organizing against the abuse that they face and that they will face “progressive discipline” in the future for similar actions. The latter contradicts CDCR Spokeswoman Terry Thorton who stated on record, “There are no punitive measures for inmates refusing to eat.”(3) In typical repressive fashion, the state responds to complaints of torture committed by state employees with outlawing any form of protest by the victims. It just goes to show that their efforts to maintain “security” have nothing to do with safety and everything to do with social control.

It’s also important to note that the best public offer coming from the state right now is that they might move away from gang affiliation charges and focus on actual rule violations as justification for throwing someone into a torture chamber. Within U.$. prisons the First Amendment is generally ignored and any form of expression or organizing not sanctioned by the state is considered against the rules. But even this reform has been on the table for a long time with no action. According to the 2004 Castillo court decision, which took 8 years to litigate, the CDCR committed to providing logical justification that evidence used to put someone into SHU was criminal in nature. Yet nothing has changed, as the lead attorney on the case, Charles Carbone, asserted at the August 23 hearing.

As Carbone pointed out, with exasperation, we already went through the whole song and dance of having hearings around the SHU with Senator Gloria Romero and the United Front to Abolish the SHU years ago. Another testifier at this year’s hearing made testimony in the 70s and 80s about the detrimental effects of isolation, but they still went on to build Pelican Bay State Prison. It is clear that the state sees the SHU as an important tool of social control and cares nothing for the destruction they cause to oppressed people.

Scott Kernan was very clear at the hearing that the CDCR would continue with the debriefing process, using confidential informants, and that they will not allow prisoners to appeal secret evidence used against them. He also said gang validations will likely continue to bring indeterminate SHU sentences. Kernan did not stick around for the public comments, and remaining CDCR staff were not given an opportunity to respond when a public commenter asked when the 5 demands would be put down in writing, after Kernan promised it would only take 2 to 3 weeks.

Lessons in Organizing

Through this process we are all learning how to organize in our conditions and what limits we face.

One of the successes of the California hunger strike was the demonstration of United Front to the masses, which inspired many to the possibilities of prison-based organizing. We do not know the details of how groups coordinated on the inside around the strike, but we do know that many groups would not be willing to sacrifice their independence to others, and yet they worked together. This example should be followed by those on the outside. We need to recognize the strength that comes in uniting all who can be united at any given time on the most pressing issues that we face. Coalition organizing strategies have held back support by not allowing a diversity of voices to come out in unity in support of the hunger strike.

Having outside pressure during a food strike is crucial to ensuring that the state just does not let prisoners die, as they are more than willing to do if there isn’t too much noise about it. Outside organizations also played an important role in spreading word about the hunger strike that was initiated by some of the most isolated people in the whole state. But, ultimately, the state controls our communication with prisoners. Despite all the work put in by the coalition to develop an outside negotiation team, the only role the state allowed them to play was to announce when the strike had ended and ensure that everyone knew to stop. The state realized that a memo from the CDCR was not going to be convincing. Other than this, the negotiation team was not allowed any access to the prisoner negotiators.

In ULK 21, we made it sound like the strike was over for beanies, calendars and proctors and some empty promises of change. This was the information coming from the outside negotiating team and the best information anyone seemed to have. Frustration with the outcome immediately started coming in and we fear that disillusionment may have followed. But this is what the SHU is designed for. This is why SHU inmates can’t call people on the outside. This is why the press is not allowed in California prisons. Misinformation would be much harder to spread otherwise. So overcoming these barriers is part of what we need to learn here.

We need to learn to build protracted and sustainable battles. There are no quick fixes, and prisoners can’t rely on the mainstream press or outside organizations to come in and rescue them. Recently, Pelican Bay censored MIM(Prisons)’s study pack on organizational structure. They recognize the importance of such information for prisoners to really get organized and exert their rights. As much as they want to label us a “security threat group” for doing it, MIM(Prisons) continues to struggle for our right to support prison-based organizing. For it is the prisoners who have the drive and determination to make the changes that need to be made to end this oppressive system.

Campaign info:

California Strike Against Torture in Prisons - 8 July 2013

Related Articles:This article referenced in: