Ongoing Discussion of Recruiting Best Practices

This issue of ULK is a follow-up to issue 63 (July/August 2018), which dove into the question of tactics around engaging people in our movement. We often see in these pages why we need to engage in revolutionary politics, who we should be working with, and what campaigns we need to work on. What is often lacking is how to get people on board. In 2018 we dove deep into this question, and this ULK is part of that ongoing conversation.

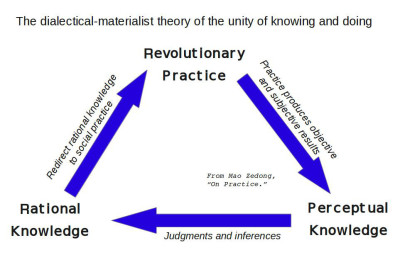

Some of our learning about effectively teaching and recruiting others can come from historical practice. We can look at what the Black Panther Party did to attract people through their Serve the People breakfast program which included political lectures during the free meal. And we can learn from the Chinese Maoists who helped people in prison learn from their mistakes through the process of group discussion and re-education. We learn from the Chinese peasants who, after the revolution was won, saw that many poor peasants were still afraid to speak out against religious leaders who had brutalized and exploited them. A few individuals led by example, attacking not the religion but the actions of these leaders, and this inspired others. We take lessons from the Communist Party of Peru in the 1990s who mobilized the indigenous countryside into a structured resistance movement that also provided education and health care services to its communities. There are many revolutionary movements that provide great examples and inspiration for our work today. (If you would like to study these revolutionary movements, send us some work to trade, or ask for a price list of books available.)

Studying revolutionary history, and particularly the practices of those communists, can give us some great ideas that we can apply to our own practice. But we also need to evaluate our own work and look for what is relevant in our current conditions. Doing this together, through the pages of ULK, will help everyone learn and improve their organizing, education and recruiting.

We can start by looking at our own persynal histories and how we ourselves were recruited into revolutionary politics. Below, the comrades in Arkansas and Maryland outline their lifetimes of political development, which are common to many letters we receive from our subscribers.

An Arkansas prisoner: I first started learning about the struggles of being a minority from my mother who raised my siblings and I in a strong Black Power presence household. Throughout my childhood we were homeless a number of times, and the system didn’t provide any alternatives for us. Instead, all the so-called programs they provided were to keep us dependent on them, and remain in the revolving door of helplessness. So I learned early that we were living in a broken system.

As I got older, I studied books like The Willie Lynch Letters, The Making of the White Man, and studied the Black Panthers. But I was too young to join the NBPP, so I became affiliated with the Crips. The problem was we were screaming “community restoration in progress,” but we were destroying more than we were building. After some years I realized that we were on the wrong path. I then became a Muslim.

I was always taught the Muslims were the pillar for the Black community. However what we lacked was political experience, or basic knowledge of politics. As I became incarcerated I was having a conversation with another brother about “Black Beauty over White Beauty.” Somebody overheard our conversation, and pulled me to the side asking if I ever studied Marxism-Leninism-Maoism. I hadn’t, and that was the starting point of me being laced up with the knowledge of socialism.

That was two years ago, and I’m proud to say I’ve came far in my journey on self-development so I may be able one day to greatly assist in community development. I’ve been able to steer a few brothers on the development of self so they one day will be able to aid our people in our struggles.

A Maryland prisoner: Since I can remember I always had a natural rebellious reflex instinct for injustices dealt to people of the struggle. Growing up in the slums of East Baltimore it’s virtually impossible to not have a leftist political perspective once you educate yourself. In inner-city life, especially an inner-city that is mostly populated by Negros, the evidence of oppression is clearly overwhelming.

I was fully turned on to revolutionary politics after Freddie Gray was assassinated by the Baltimore city police department. That incident alone sparked strong emotions in me that I’ve never felt before. I felt as though Freddie Gray could have been me or any other youth from Baltimore, which I think is true. I was incarcerated when the Freddie Gray assassination took place, then I was released probably about a month later.

At the end of 2015 I was back incarcerated again for a physical altercation with two Baltimore city police officers. Since being incarcerated this time I’ve sharpened up on my political consciousness. Most of my days are spent on studying my religion, politics and the history of the Negro people. I cannot stand to see people being oppressed by the “power-to-be” and I wish I could somehow extend a helping hand to every political injustice forced upon the people in the struggle.

Another Maryland prisoner adds: I became a Revolutionary Conscious Citizen of the Republic of New Afrika about 2 years ago. It made me totally awake! Each day i stride forth in knowledge, understanding and wisdom of my great Ancestors. I was recruited by a dear friend who watched my character and actions and revealed to me another side of life and how to truly make a difference. He showed me how the universe moves and how colonization, capitalism and imperialism destroyed nations and lives and how neo-colonialism is nothing but us uniting with our oppressor! How patriarchy grasped our minds and interacted in our way of lives in our daily actions!

I can honestly say i came a long way, yet i know that the community is more important than the individual. And as a New Afrikan Communist i overstand that everyone has the chance to change through learning and relearning through a revolutionary education. Yet, comrades, the brothas where i’m at – it saddens me! They walk around like walking zombies high off the K.

Yet i know George Jackson said: The ruling clique approaches its task with a “what to think” program; the vanguard elements have the much more difficult job of promoting “how to think.” Thus it’s our job of building consciousness to our dumb, deaf and blind Brothas and Sistas! Like Johnathan Jackson said, “Some of us are going to have to take our courage in hand and build a hard revolutionary cadre.” We can’t give up, continue the struggle! Build to win! Can’t stop won’t stop!

MIM(Prisons) adds: A lifetime of persynal experience being oppressed in the United $tates naturally leads us toward revolutionary politics. Our dedication doesn’t appear overnight with our first exposure. Some incidents, like the murder of Freddie Gray, make a stronger impact than others. But repeated exposure to oppression, and resistance, is what leads us to make the struggle our own. A strong parent or a good mentor can make a huge difference. Working as educators, we can still be very effective even if it’s just one of us working with one recruit.

Some people assume that since you were recruited, that you somehow now possess an inherent ability to recruit others. Just because you’re interested in a topic and want to contribute doesn’t in any way imply that now you have the skills to do so. What to us (the recruit) looked and felt like a normal conversation, to the organizer or recruiter is actually a work of art. It takes time and effort to become an effective organizer, not just agreement with a line.

One way we can become better organizers is to reflect on our own practice. Below are letters from a variety of contributors on this topic.

The first Maryland prisoner continues: In this prison I can relate to most dudes because we’ve had somewhat a similar journey of hardships growing up. At the same time most dudes understand and can comprehend the very conditions of oppression, but show no signs of resistance to the ill forces of the oppressor. It literally will be a handful of brothers who’ll stand up for the whole tier if these pigz blatantly disrespect or mistreat another brother(s). It is peculiar to me that most times the brother(s) that is being disrespected or mistreated will not stand up for himself, but will not hesitate to bring harm to the next brother(s) if he even so happens to think about looking at him wrong.

Each time it’s time to take a stand I’m usually right on the front lines, me and a few other brothers. We try each and every time to obtain some type of unity amongst ourselves against these pigz. I slowly but surely engage in political conversations with certain brothers to try to analyze their perspective and teach them a few things based on the same struggle we’re in. Some brothers gathered a selfish outlook on the struggle because they’ve felt as though why should they stand up for other brothers who don’t want to stand up for themselves or yet anyone else.

Due to the fact that there’s constant tensions brewing between brothers of different gangs, the unity level is at an all-time low. Meanwhile, these pigz set up “smoke screens” to delude brothers of what oppressive techniques they’re putting into motion. I try to stress that point over and over again to brothers around here but it’s to no avail. By me being the person I am, I can’t let certain or every failure in progress to justice for the struggle stop me like other submissive brothers. It is my revolutionary duty to stay positive, encouraging, and consistent.

Now, as far as the outside society, I’ve put together a blueprint to help the community to be self-sufficient. That’s why during their time of me being down I’ll continue to educate myself and strategize plans for the struggle ahead. In conclusion, this is my brief elaborate story of “how I was recruited.” I greatly appreciate anyone who takes the time to read this piece of material. All Power to the People.

MIM(Prisons) adds: This comrade consistently maintains a positive and encouraging outlook. Any insight on how one goes about doing that is always appreciated, as we all get discouraged sometimes and can use a reminder on how to stay up. As for not understanding people’s inconsistencies in what they accept vs. fight over, i have some questions for reflection:

Has there ever been a time in your life when you were like one of those brothers who doesn’t stand up for emself against the pigs, but will bring harm to another persyn? What was your own thinking behind that behavior? What were you afraid of? Can answering these questions about our own histories help us have a better understanding of (and more effective conversations with) people we’re trying to get on board?

I also have some questions about standing up for people who won’t stand up for themselves, which is a common complaint. I’m curious if there’s a way to find a middle ground on this. In one way, we are doing the whole prisoner population a service by defending people and not letting the pigs get away with anything. But on the other hand, we are enabling people’s inaction because we’re doing the hard work for them. How can we enforce some, even minor, participation from the people we’re helping?

For example, MIM Distributors has a policy about writing letters to administrators when our mail is censored. If we had more resources, we would protest all censorship of our materials. At this time, we only write letters on behalf of people who are also appealing the denials. Part of it is about our limited resources, and part of it is about not going to bat for people who aren’t going to stand up for themselves, or us. Same with our Prisoners’ Legal Clinic, Free Books for Prisoners Program, etc. We ask for some kind of participation before putting extra resources into people.

A big benefit of this approach is it helps distribute our limited resources so the people who are putting in work are getting some attention from us. It also functions to hold people to a high, yet reasonable, expectation. We aim to be supportive, and demanding, and we believe this approach will do the most to build participation and leadership.

A Missouri prisoner: In this struggle I recruit by being willing to spot for you on yo bench press, even though my thing is the elliptical machine. I am willing to only listen when you need to do all the talking. I am able to be the one whom doesn’t have to be “right” when wrong is of no consequence!

I feed off of the energy that is already in existence! I know gangs, religion, drugs, prison politics, music, nationalists, highways, vehicles, food & find our connections. And the best part of it all is I’ve recruited a comrade and not divulged a single plan yet!

reddragon of USW: Having different convos here and there it dawned on me that I was able to engage others based upon certain interests, and that in the past my attempts were fruitless based upon my inability to understand that approaching political ideology/ theory from one side only was the reason the convos bore no fruit!

Therefore i conducted a simple personal experiment in which I engaged different persons from different angles based upon their interests. For example, one brother is interested in business administration, another in talking about military strategies/tactics, etc., and another in music and the arts. All of these things have a place in the revolution. After the seizure of power we will no doubt need planners, administrators, as well as many other positions once held by the bourgeoisie and the former oppressors. So by interjecting communist thought into convos about a new society we can create certain sparks. There are those who feel inadequate in certain areas that they feel are too complicated so they shy away. So approaching them from angles of particular interest is something to think about.

Comrades, let us prepare with a sense of haste. As the conditions become ripe, as economic crisis and the threats of war with a major power looks imminent, the time may come sooner than we think.Dare to struggle, dare to win, all power to the people! Victory is ours! In solidarity I remain!

MIM(Prisons) adds: What reddragon and the comrade from Missouri have in common is meeting the potential recruits where they’re at, and engaging them on what they are already interested in, while relating it to the revolutionary movement. The California comrade’s approach, below, is slightly different. Ey gets into a single tactic, rather than an overall approach, that ey uses in conversations with potential recruits.

A California prisoner wrote: When it comes to people and you’re trying to impress upon them a particular concept or an idea, sometimes the direct approach isn’t the best tactic. So #1, when having a conversation with them, we utilize the ask-and-answer approach to see how much they know, and how receptive they are to the topic at hand.

Because for the most part, uneducated people are negative and close-minded. They become argumentative and want to express their viewpoint in order to appear right and that they know what is correct. But the truth of the matter is they know absolutely nothing.

So, the question and answer approach, in a sense, will expose them. This will put you in a superior position to teach them without any opposition. And now they know that they can learn a great deal.

However, through this Q&A tactic, you’ve now piqued their interest in a profound way. Hence, becoming receptive and open-minded to knowledge and understanding about revolutionary change. This is the greater reality for us socialists who doesn’t fear the movement of teaching what life is, and that a society without imperialism is possible.

MIM(Prisons) adds: This tactic coming out of California is similar to the Socratic method, which has been used for thousands of years to test our implicit beliefs and present analysis. It helps expose the errors in our thinking so that we can work through them and come to a deeper understanding. If we approach the debate head-on, the dialectics inherent in a conversation will have us arguing our side with the other persyn going even harder arguing eir side. It takes a lot of humility to give up one’s argument in this type of conversation, and often leads to a dead-end debate or escalation of tension.

While i agree with this comrade’s approach in using questions to help the persyn see the errors in eir thinking, one major thing i would adapt about the approach would be to see these recruits more as friends, rather than adversaries. We have no interest in teaching people “without any opposition,” and we certainly don’t believe that people who are uneducated “know absolutely nothing.” They might not be educated by bourgeois institutions, or even in political philosophy or history. But imprisoned masses have a lifetime of experience in living oppressed in bourgeois society. Rather than knocking people down, to be receptive to our “wisdom,” we want to help open people up and get us learning together. Certainly there are occasions to just go at someone who’s being loud and ignorant, but we don’t want to do it as a general rule.

Another part of recruiting tactics is choosing who to focus on, by identifying who we’re likely to have the most success with. There are probably lots of different views on this, and below is one comrade’s method. The details of who we aim to recruit are likely to vary depending on our own strengths and weaknesses as an organizer, as well as the conditions where we’re at. We’ve received many letters that contradict some of the principles below, so we don’t hold them as hard rules for all organizing.

A Texas prisoner: There goes a lot into recruiting people into Maoism. Once I have overcome the social stigma of communism by instead calling it “Maoism,” I have overcome one barrier. Like the word “Islam,” it is too taboo a subject.

I treat and focus on each individual differently. I look at variables of my peers. Is my cellmate young or old? Is he poor or rich? Is he antisocial or outgoing? Is he educated or uneducated? Many things go into approaching someone and a good place to start is with my cellmates.

A young cellmate is easy to guide. That is why gangs approach the youth. Instead of older individuals, the young person has not been “burnt out,” has not had so many bad experiences in politics, as they are inexperienced. The youth naturally enjoy to rebel. Most young prisoners are here because of the capitalist systems’ manipulation in laws. So they yearn for a revolution of change. The older are too mundane or too frightened to rebel. Or they do not wish to get off their butts and demonstrate. Rather than participate in capitalism, they should try Maoism, I teach them.

The poor prisoners think of their oppression with disdain. The poor prisoner understands the struggles of poverty. They already know that capitalism has stacked the laws against them. Most prisoners have or own little property. Though most prisoners have labored, there was never any relief from poverty. I explain to them that under a Maoist system of government all property would belong to the workers/laborers. And that most of the elite are rich because others labor for them. Though participating in the status quo, the laborer is exploited. Maoism would abolish this system, I teach them.

An outgoing prisoner is preferable to the cause because they are out and about. The behavior could be cultivated into political work or demonstrations. An anti-social prisoner is often oppressing other prisoners, while hindering his peers. He is not ideal for the movement. They are difficult to work with and not worth the trouble.

I use the educational material provided in ULK to recruit and teach my people. The most uneducated person with a drive to learn is never a waste of my time. I enjoy taking the time to explain the examples of capitalism and Maoism. There are many questions a curious, young person might have and a outgoing individual should be more than happy to explain. Never the less, patience is a virtue.

And finally I believe that I should start with my cellmates first because they are here and available. I can show what I preach.

My ideal recruit would be a young, poor, uneducated but willing to learn cellmate. As of this writing, I am recruiting my current cellmate. I am not perfect but I am hopeful that my quest is the right path.

MIM(Prisons) adds: We encourage all our readers to go to this level of thoughtfulness about their recruiting methods. Complaining to MIM(Prisons) that “nobody is interested” is partly an admission that you have a lot more work to do to develop into an effective organizer. The effects of bourgeois capitalism on our recruiting base give us real, hard challenges to our efforts. And with centuries of practice, the U.$. criminal injustice system is very skilled at frustrating any movement toward justice, progress, or revolution. It’s a tough job, but the more we practice at it, the easier it gets.