Stanford Prison Experiment, and Just Doing My Job

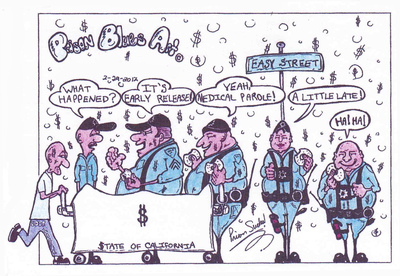

not value the lives of prisoners in the United $tates.

In the Stanford Prison Experiment (1971) students were assigned roles as guards and prisoners in a simulation, and soon both groups took on the typical behaviors of those roles, with the guards treating the prisoners so harshly that the experiment was stopped early. MIM(Prisons) has used this as an example that oppression is systematic and that we can’t fix things by hiring the right guards, rather we must change the system. In ULK 19, another comrade referred to it in a discussion of how people are conditioned to behave in prisons.(2) The more deterministic conclusion that people take from this is that people will behave badly in order to conform to expectations. The Milgram experiment (1963) involved participants who were the “teacher” being strongly encouraged to apply faked electric shocks to “learners” who answered questions incorrectly. The conclusion here was that humyns will follow orders blindly rather than think for themselves about whether what they are doing is right.

“This may have been the defense they relied upon when seeking to minimize their culpability [31], but evidence suggests that functionaries like Eichmann had a very good understanding of what they were doing and took pride in the energy and application that they brought to their work.(1)

The analysis in this recent paper is more amenable to a class analysis of society. As the authors point out, it is well-established that Germans, like Adolf Eichmann, enthusiastically participated in the Nazi regime, and it is MIM(Prisons)’s assessment that there is a class and nation perspective that allowed Germans to see what they were doing as good for them and their people.

While our analysis of the Stanford Prison Experiment has lent itself to promoting the need for systematic change, the psychology that came out of it did not. The “conformity bias” concept backs up the great leader theory of history where figures like Hitler and Stalin were all-powerful and all-knowing and the millions of people who supported them were mindless robots. This theory obviously discourages an analysis of conditions and the social forces interacting in and changing those conditions. In contrast, we see the more recent psychological theory in this paper as friendly to a sociological analysis that includes class and nation.

As most of our readers will be quick to recognize, prison guards in real life often do their thing with great enthusiasm. And those guards who don’t believe prisoners need to be beaten to create order don’t treat them poorly. Clearly the different behaviors are a conscious choice based on the individual’s beliefs, as the authors of this paper would likely agree. There is a strong national and class component to who goes to prison and who works in prisons, and this helps justify the more oppressive approach in the minds of prison staff. Despite being superior to the original conclusions made, this recent paper is limited within the realm of psychology itself and therefore fails to provide an explanation for behaviors of groups of people with different standings in society.

We also should not limit our analysis to prison guards and cops who are just the obvious examples of the problem of the oppressor nation. Ward Churchill recalled the name of Eichmann in his infamous piece on the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center to reference those who worked in the twin towers. Like those Amerikans, Adolf Eichmann wasn’t an assassin, but a bureaucrat, who was willing to make decisions that led to the deaths of millions of people. Churchill wrote:

“Recourse to ‘ignorance’ – a derivative, after all, of the word ‘ignore’ – counts as less than an excuse among this relatively well-educated elite. To the extent that any of them were unaware of the costs and consequences to others of what they were involved in – and in many cases excelling at – it was because of their absolute refusal to see.”(3)

The authors of the recent paper stress that the carrying out of something like the Nazis did in Germany required passionate creativity to excel and to recruit others who believed in what they were doing. It is what we call the subjective factor in social change. Germany was facing objective conditions of economic hardship due to having lost their colonies in WWI, but it took the subjective developments of National Socialism to create the movement that transformed much of the world. That’s why our comrade who wrote on psychology and conditioning was correct to stress knowledge to counteract the institutionalized oppression prisoners face.(2) Transforming the subjective factor, the consciousness of humyn beings, is much more complicated than an inherent need to conform or obey orders. Periods of great change in history help demonstrate the dynamic element of group consciousness that is much more flexible than deterministic psychology would have us believe. This is why psychology can never really predict humyn behavior. It is by studying class, nation, gender and other group interests that we can both predict and shift the course of history.

Related Articles: